Learn from the Chicken.

September 2022, Tokyo.

We met Isabella Stefanelli again. Instead of squeezing everything into a schedule chased by time, we sat down peacefully, and talked about the things people are curious about her — and the ones that truly matter.

We began with yarns, looms, and sewing, and moved on to rest, time, memories tied to different places. We also asked her about her teacher, family, and elements of nature that have left marks on her life. Isabella spoke slowly about how she let emotions enter her fabric, how living in different cities affects her inside, and how she translates life experiences, feelings, and sensations into the shape of garments.

This is a long conversation, and it was written slowly. We hope you enjoy it.

Part 1

Process: The Fabric's Voice

Q1

Could you walk us through the whole process of making a garment? From yarn to a finished piece?

I select yarns, decide what to do based on my feelings, sometimes I twist them or in Season XVII I have used fabric strips and I ask myself: how can I turn them into something that holds my feelings? I chose warp yarn yarns accordingly. Techniques only matter if they give something back emotionally; they're secondary to feeling. However the process is not always the same. I do not follow a strict mental process. I can not give away a rule. It does always change.

I also mix fibers based on their behaviour and my feelings about it. I combine them and something happens — that unknown is interesting. Cotton behaves differently depending on its source and twist (high/low, heavy/light). Much of it is educated guessing. On the loom, fabrics look rigid and similar — thick or fine yarn can seem alike while weaving. Only after washing do they reveal their true character. That's when you really understand the fabric.

It's like cooking: the soup is nice, then you add lemon or pepper — or you change the wash temperature — and small changes transform it. Once the fabric is right, I know which garment it belongs to. My base patterns are deliberately simple so the fabric has space to speak. However that is simply my language, it comes natural to me.

Yarn playing

Q2

What's the most time-consuming part?

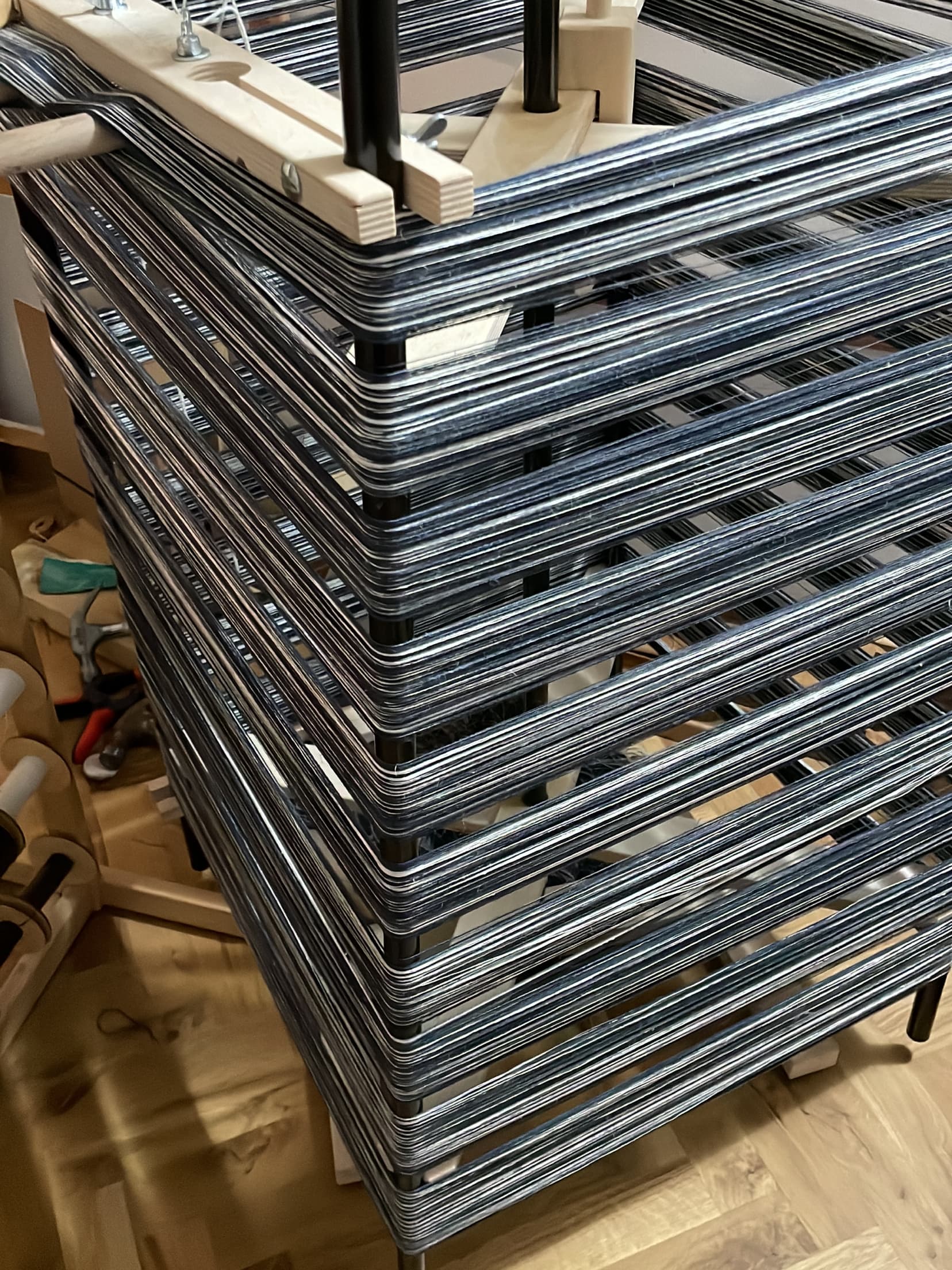

Weaving, certainly. Setting the warp is very difficult — getting the tension right is crucial. Depending on the method, preparing the warp can take 15 days to a month. If I have a 100-meter warp, I might weave about a meter a day. A single fabric might use 1500–2000 ends, each needs the right tension; sometimes I have to add weights to individual ends. It's complicated. And guiding the whole from weaving to hand sewing to knits. When you do everything with care, anything takes time. It's undeniable.

Warp setting

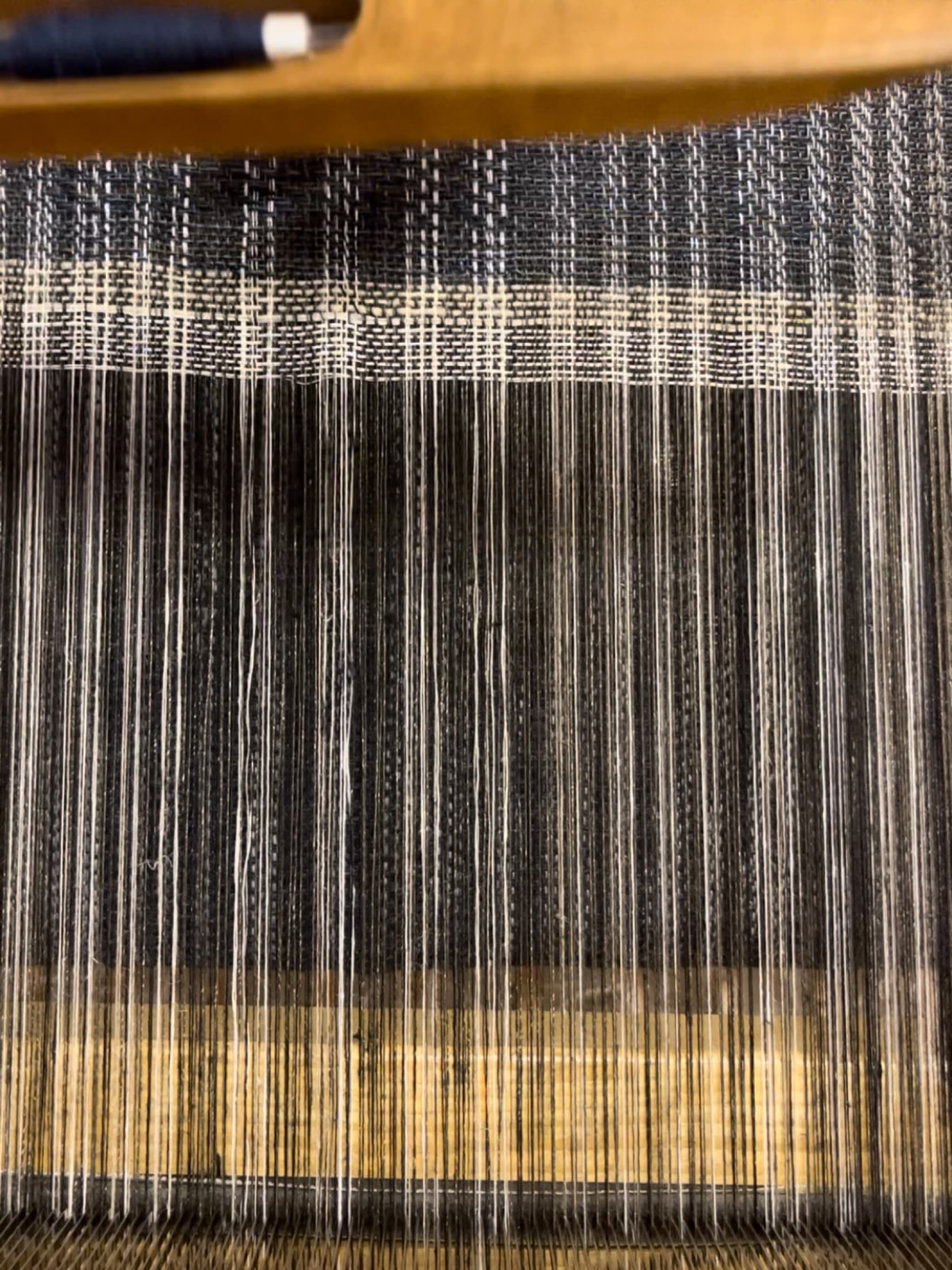

Warp testing

Sampling weaving

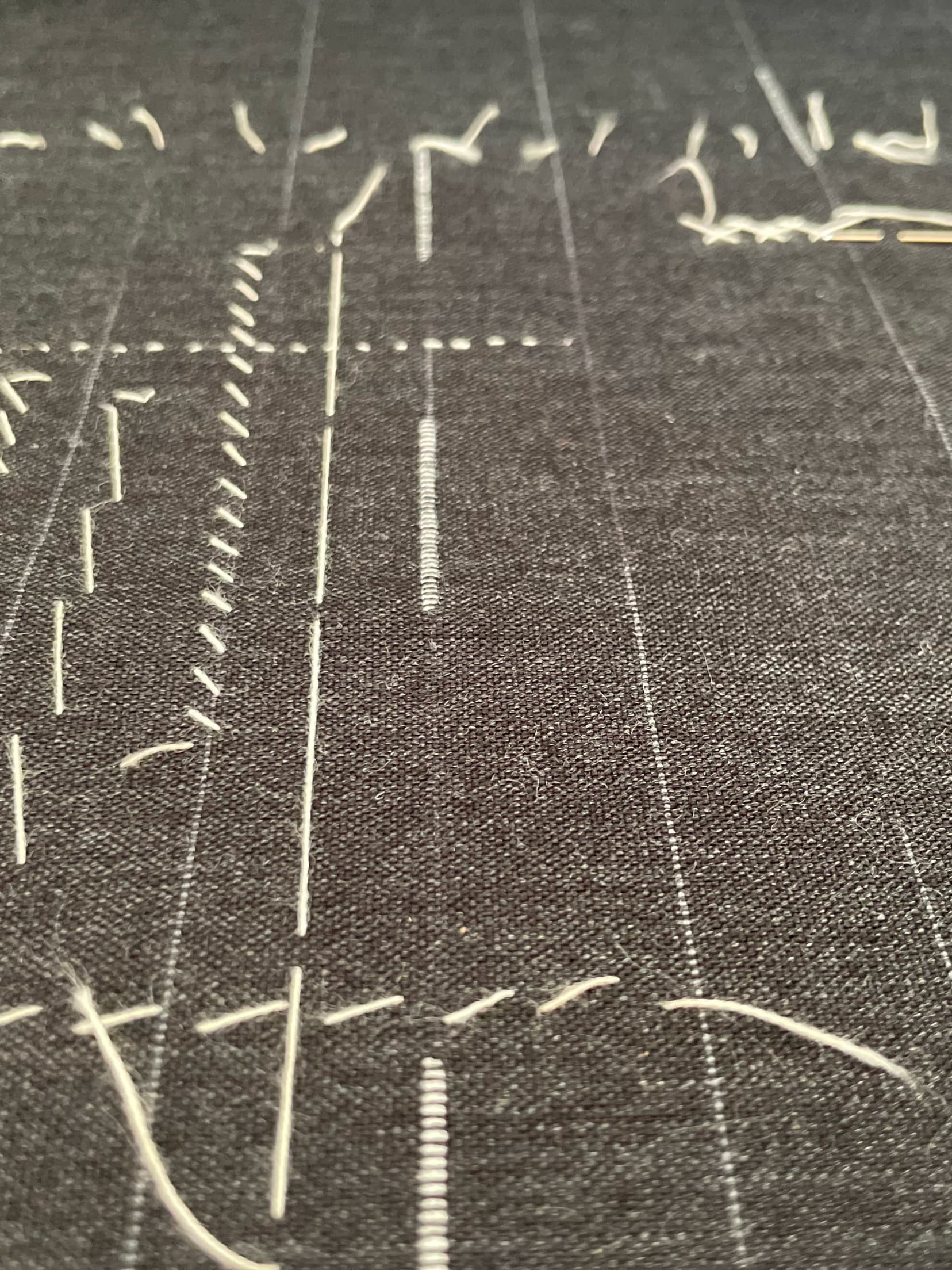

Tailoring stitch on designed fabric

Q3

So it's not easy for other weavers to repeat your designs.

My fabrics are mine, they are complex, difficult to repeat, yes, and it is the feeling that holds the emotion. Fabric weaving acts as a release of feelings, and apart from the design itself, having my own production in house let me guide the weaver through, without interrupting the flow and this makes the cloth very personal. No one can repeat the same. You well know that even painters that try to copy each other or compete, they always produce a different feeling and the frame looks different. We are all unique, and yes the fabrics construction and technique are very much challenging. The whole creates a unique product indeed.

![Fabrics from season XVI [Re-View]](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fs3.ap-southeast-1.amazonaws.com%2Ffraw.cn%2Fassets%2Fuploads%2Flearn-from-the-chicken%2Foa-image-9.jpg&w=3840&q=75)

Fabrics from season XVI [Re-View]

Q4

How about the other part — the pattern design?

Pattern cutting is something I developed over time. It's playful for me — I enjoy making shapes. I once worked as a professional pattern cutter, which is a very difficult type of work. I'm 52 now and have been sewing since childhood; I've worked a lot, so certain steps feel easy to me today, though they may not be easy for others.

And beyond pattern cutting, the next stage — sewing — is a completely different matter. Sewing requires a high degree of sensitivity. Every fabric has its own character. The same stitch can look different depending on the tension, the sewer's mood, even the weather of the day. Many people think sewing is purely aesthetic, but seams must be strong, durable, and able to withstand washing. Your two hands are the real tools, and they must learn to work together. It takes years to master this. Honestly, I think one can learn weaving faster than truly mastering sewing.

Q5

What does it feel like to master every step?

I feel it is necessary if I want my work to pass on my feelings. I do follow each stage very closely including knitwear. It is all very sensitive: I must follow the knitters, give them feedback, specify needles, and correct techniques, and it is a continuous learning. If I don't, shortcuts appear and the piece changes. My work needs personal oversight; otherwise, it becomes something else. It's like a workshop: if you don't watch carefully, steps get skipped. With the loom, you must understand the instrument; with sewing, your own hands are the tool.

Handsewing is a laborious skill, and it's never easy to find people who truly sew well.

Isabella's tools - needle, thimble, her father's scissors

Isabella sewing buttons

Q6

A totally different experience compared to working with a factory?

For me, the joy begins when the garment “speaks” — when it carries its own presence and soul. That is the moment I love most. I enjoy choosing materials, but I also love when collaborators become curious and engaged, suggesting ideas rather than just following instructions. I've always been very product-driven, and while the process can feel daunting, this is precisely where my happiness lies.

Part 2

Inner Landscapes: Where Shapes Come From

Q7

Do you think of menswear or womenswear when designing?

No, I don't. I see character, mind, and soul, rather than sex or physical characteristics.

Q8

Many labels on your clothes reference artists and writers — how do they connect to your garments?

Shapes often come from artists who live in my mind. My father was a painter, and we had many art books at home. I would read about their lives and emotions —their childhoods, their struggles, their words — and translate those feelings into shapes. Virginia Woolf's stream of consciousness inspired a flowing piece; Modigliani's sculptural forms suggested a long, elongated jacket. Each person brings a shape, and then the fabric adds another layer. We all contain many personalities, and I like to reflect that through layering.

Even writers influence me. William Carlos Williams, for example — he was actually a doctor. His poetry is simple, sharp, almost surgical, yet deeply emotional. I admire that restraint and depth, and I try to let the fabric “tell” in a similar way.

So when I design, especially with fabric, I need to let the child in me play. It's not superficial but very deep, and for that I need my own space — a safe place where that child can freely experiment.

Virgina Jacket inspired from and named after Virgina Woolf

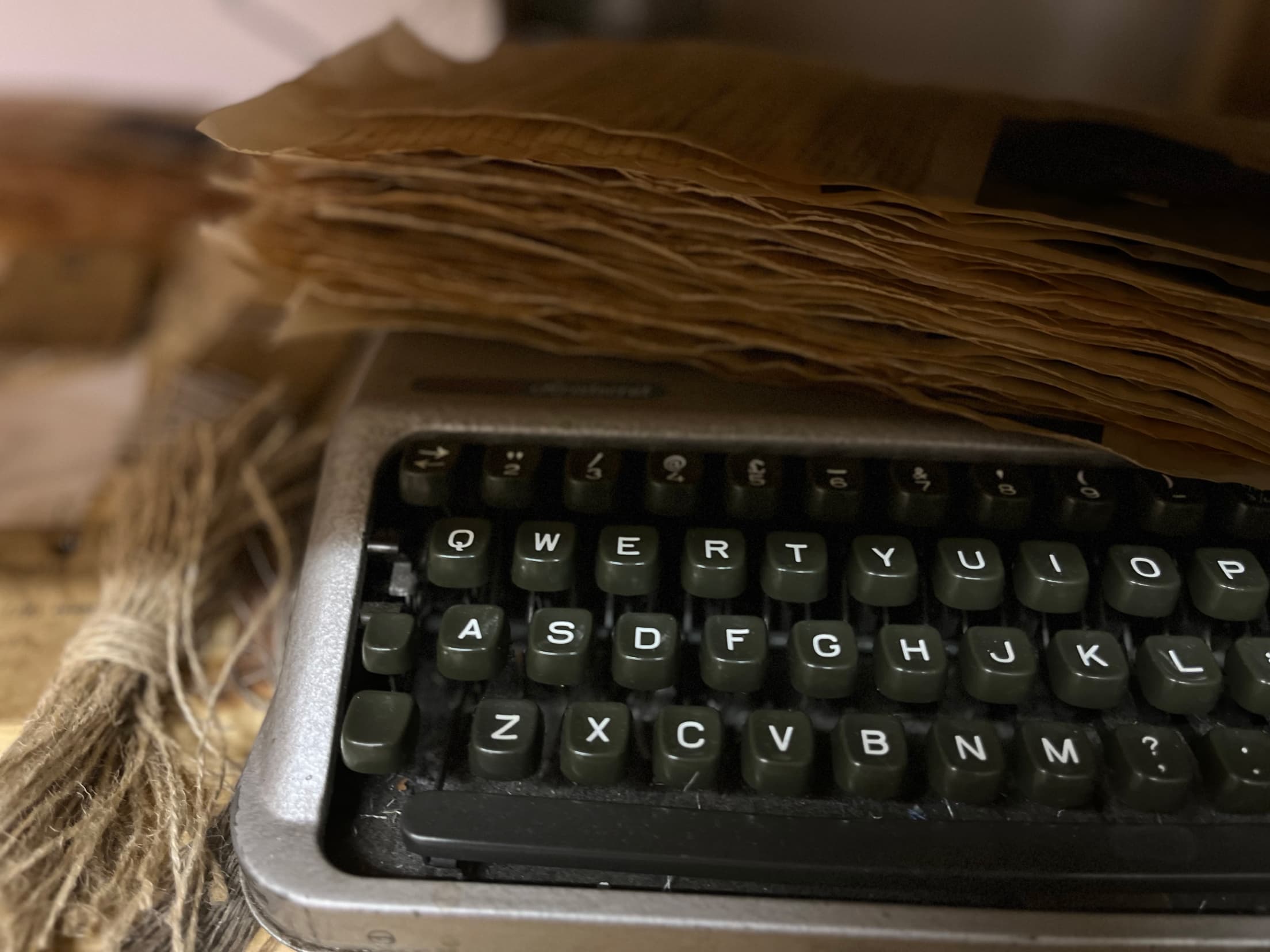

Preparing handmade labels using her typewriter

Q9

You mentioned your textile teacher — you named a loom after her, what is the story?

Nancy. Nancy Martin Stetson. I hadn't spoken about her for a long time until recently. She was an American artist and textile teacher I met during university in a medieval Italian town. She had traveled to Indonesia and Japan. Her partner, Gianni, Gianni Pezzani, is a photographer from Parma. Both were important to me.

After graduation I moved to Milan because of Nancy, and worked with her. She opened a new way of seeing textiles and guided me spiritually during one of the most difficult times in my life — physically and mentally. My best friend from school, Noriko, also supported me. On Sundays we cooked ravioli at Nancy and Gianni's, walked their Jack Russell, called Incy, read newspapers—she liked reading old ones, to stay in touch with the past in a way. She discovered I could sew and encouraged my first tailored pieces for Gianni — trousers, jackets, shirts. Later, I dedicated a loom to her. She remains a big emotional part of my story.

Part 3

Roots and Resonance: Threads of Belonging

Q10

You moved into your current studio during the last collection [Passage]?

Yes. It was about moving and transitioning. I did a lot of personal work — breathing practices, emotional work. With help, I learned to open up; I hadn't exposed much of my emotions before. That inner work gave me strength and clarity, which then translated into my collections. Each collection carries themes — imperfection, acceptance, being true to oneself. It's an ongoing development, not a single passage. I'm still looking for the right place; I'm still searching.

This kind of transition is not only about physical space but also about my inner self. I'm always trying to become clearer. I like to understand myself — digging deeper helps me not only to improve as a person but also to build better relationships. Making time for myself is essential; if I don't, I simply cannot create.

Isabella's London Studio in Stratford

Q11

How do you think about time — your rhythm and your breaks?

Time is very strange. Sometimes it moves quickly, sometimes unbearably slow. A week in London feels different from a week in Japan. When I weave, time even vanishes — the process is so slow, yet suddenly the weaver perfects something and progress feels incredible. Time is emotional. Clocks are not the truest measure; the sun and seasons are.

I try to take breaks, to recognize them as a human need. Without them I lose perspective, get too deep into the product, and can't see what needs to change. When I take time off, I go to the park, reconnect with nature, or meet like-minded people. Ideally, I travel — new experiences recharge me. Human connection matters deeply. I feel everything is connected — from stones to animals — and I don't draw sharp distinctions between them.

Q12

Different places awaken different sides of us.

That's the fascinating part. Different places allow us to express different sides of ourselves — just as languages unlock different emotions.

I was born in southern Italy, into a family of farmers on my mother's side and a father who was both an artist and a tailor. Life was simple: my aunty chickens in the yard, evenings when women embroidered and talked in the street. The houses there are built of "Pietra Leccese", a stone sourced locally — a sandy yellow, porous yet strong. Their high, vaulted star-shaped ceilings trapped the heat above, keeping the rooms cool. We lived around a courtyard with a rainwater well and a stone basin for washing.

Food was equally simple yet full of flavor — olive oil, tomatoes, bread, vegetables and fresh eggs! There were also influences from the Middle East and Greece. Everything came from the garden, and those tastes shaped me.

Later, London offered a different experience. Its multiculturalism creates a common language, breaking the authority of any single tradition. I love that, though I often miss the simplicity of the south. Japan, on the other hand, draws me for its spirituality, simplicity, and respect. Even as a child, I preferred sleeping on the floor - it made me feel closer to the ground, more connected.

My aunt used to tell me, 'Watch the chickens and learn.' That simple lesson from nature has stayed with me. Wherever I go — whether Italy, London, or Japan — I carry this belief: that nature itself teaches us how to live and how to behave with others.

Pietra Leccese

Olive trees and Cacti

Summer in Salento